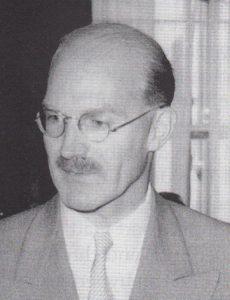

Gordon Wolstenholme was a distinguished physician and medical administrator, a man of great personal charm whose outward gentleness concealed a steely resolve and an unswerving dedication to those objectives which were close to his heart. He became internationally famous for exploring new ideas in medicine as the firmly independent director of the CIBA (now Novartis) Foundation for three decades. This, however, was one of the main strands in an enormously productive involvement with medical organisations across all disciplines that continued throughout his life.

Born in Sheffield, the son of a mechanical engineer, he studied at Repton School in Derbyshire, at Corpus Christi College in Cambridge and at the Middlesex Hospital Medical School. In 1939 he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps, where, because of his interest in haematology, he finally became director of the Allied Blood Transfusion Services in the Mediterranean, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. By 1944, he became the commanding officer of a military hospital in northern Italy and was responsible for all resuscitation services in the Mediterranean sector, whilst also overseeing the distribution and first large-scale use of penicillin in that region. He also spent some time in Yugoslavia training doctors who were serving with Tito’s partisans and providing medical supplies to the various groups fighting in the notoriously difficult terrain of that country. It was through this work that he met his eventual second wife, Dushanka, a doctor who had trained in Belgrade. She went back behind the lines in Yugoslavia and, with Gordon’s help, arranged for medical and other supplies to be dropped to the partisans, and they exchanged letters by various precarious routes. At the end of the war, this chance meeting was translated into marriage and a powerful peacetime partnership. In acknowledgement of Gordon’s outstanding services in the RAMC he was awarded a military OBE in 1944.

When he left the RAMC in 1947, Wolstenholme considered the possibility of a career in haematology. However, the Swiss pharmaceutical company CIBA decided to set up (as Anthony Tucker described it in his obituary in The Guardian) an independent centre in London to help repair the war torn fabric of research in medicine and biology, partly because of British resistance to Nazi ideology and partly because, uniquely in Europe, under English trust law a charitable organisation of this kind could have total independence from its sponsor. From the outset it was realised that some individuals working in research and academic communities would be suspicious of commercial subsidy. The centre needed a director and trustees whose background, position and authority would dispel all doubts about freedom from parent company influence. Hence, the organisation was designed along similar lines to the Nuffield and Wolfson Foundations. When, in 1949, Wolstenholme began work, his trustees included Lord Beveridge and the later Nobel laureates, Alexander, later Lord Todd (chemistry 1957) [Munk’s Roll, Vol.X, p.493] and Sir Howard Florey (medicine 1945) [Munk’s Roll, Vol.VI, p.178]. However, the greatest guarantee of independence came from the vigour, integrity and style of the Foundation’s activities, so clearly defined by Wolstenholme himself. The Foundation set out to organise a series of cross-disciplinary, intensive and often controversial residential symposia, involving worldwide participants. Chairmen were chosen for their ability to probe and stimulate debate, and the presentation and discussion sessions of each symposium were edited and published rapidly. Many other centres across the world envied and imitated the closed symposium framework so splendidly devised by Wolstenholme as a means of probing technical and at times controversial questions. Occasionally, he somewhat wickedly introduced a humorous component into the proceedings. At a symposium on extrasensory perception in the 1950s, participants were surprised on their final day to find that some among their number were able to perform several mysterious feats that they had come together to discuss. As Anthony Tucker says, these gifted individuals were professional magicians covertly hired by Wolstenholme to pep up proceedings; not all of the participants were amused.

Wolstenholme’s talents as organiser, administrator and the fount of original ideas were closely matched by his ability to act as a mediator and catalyst. He brought together scientists and others of outstanding intellectual merit, frequently widely separated by age, background and status and often a group who would never have debated together. Abraham White of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York described Wolstenholme’s CIBA Foundation meetings as a 20th century version of a caravanserai, a gathering of travellers at an oasis, where from dawn to dusk time would be spent matching ideas and intellects and engaging in pointed discussion. In fact, some symposia were held in the East, in India or Malaysia, and although early meetings concentrated on very narrow medical subjects, the range and breadth of the programmes increased with time. Notable was a symposium in 1956 on ‘the nature of viruses’, chaired by Sir Charles Harington [Munk’s Roll, Vol.VI, p.222], including among the participants Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin and James Watson. In 1962, a meeting on ‘man and his future’ included papers presented by Julian Huxley, Gregory Pincus, Albert Szent-Gyorgyi, Alex Comfort and Joshua Lederberg. It ended with a tour de force from J B S Haldane, who spoke on the subject of ‘the next 10,000 years’. But Wolstenholme’s taste for the broader brush was also reflected in meetings on ‘man and Africa’, ‘conflict in society’, ‘teamwork in world health’, ‘caste and race,’ ‘the health of mankind’ and ‘civilisation and science’. In the one on ‘the health of mankind’, Wolstenholme exposed his idealism in saying. “Healthcare – a world health service – is an essential step towards man’s well-being and toward a world society. If we cannot work together for the health of mankind then we are rightly doomed.”

Wolstenholme was somehow able, without apparent effort, to manage simultaneously many complex enterprises, working, for instance, on the restructuring of medical services in Ethiopia (1963 to 1974) and in Caracas, Venezuela (1969 to 1978). When he retired from the CIBA Foundation in 1978, he moved not into the country, but into the heart of London, in order to be close to the many medical and scientific organisations he served. Among the innumerable other organisations which he helped to develop were the Arthritis Research Campaign, the Renal Association, the National Kidney Research Fund, the International Society for Endocrinology and the European Society for Clinical Investigation. He also served as president of the Royal Society of Medicine from 1975 to 1977 and in 1978, and showed a lifelong dedication to the interests of that society. He was the first chairman of the advisory council of St George’s University medical school in Grenada in the Caribbean and was master of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries (1979 to 1980).

At the College, Gordon became Harveian Librarian, a post which he held with great distinction from 1979 to 1989. During his tenure he established a programme of restoration of the College’s paintings and busts, initiated the historical resources panel (an advisory panel to the Harveian Librarian) and began a programme of meetings under the auspices of the panel at which Fellows and members gave short presentations illustrating resources in the College library. He also took over the editorship of the lives of the Fellows (Munk’s Roll) and substantially improved the style of the biographies, which had often previously been rather bland. He went on to develop, with the then Oxford Polytechnic, a series of videotaped interviews with notable personages in the biomedical world. He also edited two books describing the portraits of the College.

Throughout his outstanding professional career Gordon edited or wrote many books and scientific papers and gave numerous named lectures in the UK and abroad. He also found time to chair the Genetic Manipulation Advisory Group (GMAG). He became an honorary member or honorary fellow of innumerable scientific and medical bodies in the UK and abroad and was an honorary life governor of the Middlesex University Hospital from 1938. He received the decoration ‘Lik’ from Marshall Tito in 1945, became a Chavelier de la Legion d’Honneur in 1959, received the gold medal of Perugia University in 1961 and the gold medal of the Italian Ministry of Education in 1961, as well as the Star of Ethiopia in 1966. He became a knight bachelor in January 1976 and was awarded the Linnaeus medal of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1977 and the Pasteur medal of the Pasteur Institute, Paris, in 1982.

At the age of 75, when many less vigorous men would have been resting on their laurels, his dedication to the development of medicine overseas led to his initiating an organisation entitled Action in International Medicine (AIM). This body, first established in 1988, had continued to make an outstanding contribution to the improvement of medical care and medical facilities worldwide and above all in developing countries. AIM worked towards establishing sensitive local primary and environmental healthcare in the poorest countries. The intention and hope was to achieve these objectives through assistance given to frontline professional health workers at the district level and by strengthening continuing education and postgraduate training for all healthcare professionals. 97 member institutions, including most of the professional national bodies and international medical organisations based in 32 developed and developing countries became affiliated to AIM. It was not Sir Gordon’s fault that the difficulty in raising supportive funding for AIM resulted in its activities being curtailed in 2001, but nevertheless his visionary ideas have borne fruit in countries across the world.

Despite his intensely active medical and administrative career and the innumerable responsibilities which he gladly shouldered, Gordon took time to pursue hobbies and interests in photography, music and hill walking. He married twice, first to Mary Elizabeth, the daughter of the Reverend Herbert Spackman, and had one son (who later became a captain in the Royal Navy) and two daughters. He also had two daughters with his second wife, Dushanka, who gave him tremendous support throughout his time at the CIBA Foundation and throughout his lengthy and distinguished professional post-war career.

[References:The Observer 14 April 1991; Yorkshire Post 26 June 2004; The Times 5 July 2004; The Daily Telegraph 7 July 2004; The Guardian 8 July 2004]

Courtesy Royal College of Physicians London, Munk’s Roll, Volume XI, page 633