The UK Kidney Association's (UKKA) UK eCKD Guide is derived from the NICE CKD guidelines and relevant UKKA guidelines.

It aims to provide quick online support for the diagnosis and management of CKD.

This guide was most recently updated in February 2024

UKKA statement following the 2021 NICE CKD Guideline update

Rationale & recommendations for removing adjustment for ethnicity from eGFRcreatinine

Patient information can be found at Kidney Care UK and CKD explained.

Additional resources are available here.

Contents of the UK eCKD Guide

-

Measurement of kidney function

- eGFR

- Albuminuria/Proteinuria

- Haematuria

-

- 4 variable Kidney Failure Risk Equation

- CKD Stages G1 or G2

- CKD Stage G3

- CKD Stages G4 and G5

-

Assessment of patients with a new diagnosis of CKD

- Aetiology

- History Taking

- Examination

- Investigations

-

Management of patients with CKD

- Frequency of monitoring

- Blood pressure management

- Renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors

- Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors

- Non-steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonists (Finerenone)

- Cardiovascular risk reduction

- Deteriorating renal function

- Referral to specialists

-

- Anaemia

- Mineral bone disorder (Ca-PO4-PTH)

-

- Advanced kidney care (AKC)

- Key clinical points for patient review

The UK eCKD Guide History

The current version of the UK eCKD Guide was revised in 2024 by Javeria Peracha and Paul Cockwell. It includes the most recent NICE CKD guideline update and UKKA SGLT2 inhibitor guidance.

Previous versions

The authors of the original UKKA eCKD guide were Neil Turner and Steve Blades, with the help of Deena Iskander and others (2005). This guide was subsequently revised in 2009 by Jane Goddard, Kevin Harris and Neil Turner, further revisions were made in 2017 by Simon Lines and Balan Natarajan, and by Paul Cockwell in 2019.

Definition of Chronic Kidney Disease

Definition

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) can be defined as a sustained reduction in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and/or urinary abnormalities or structural abnormalities of the renal tract.

The impact of CKD

Chronic kidney disease has a global prevalence of 9.1% and is more common in females but men are more likely to progress to kidney failure. Kidney failure is defined as GFR <15 mL/min/1.73m² or treatment by dialysis therapy. CKD increases in prevalence with age and high-income countries report more kidney disease than low income countries, probably as a consequence of both demography and under-reporting.

Where studied, social deprivation is associated with a higher prevalence of CKD. The scale of CKD and the consequences for health care delivery are profound; CKD is now the 4th most common global cause of non-communicable disease death.

Outcomes for those with CKD

The large majority of those affected by CKD never progress to kidney failure, the major clinical outcome burden of CKD relates to the major increased risk of cardiovascular disease events in those with CKD compared to those without CKD. This increased risk is directly related to the severity of kidney disease, as measured both by excretory kidney function (eGFR), so the lower the eGFR the higher the risk, and albuminuria quantified in clinical practice by albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

CKD is often referred to as 'silent'. This is incorrect. Whilst CKD does not have a clear symptom complex in the same way as other long-term conditions, persons with CKD have a major symptom burden including severe fatigue, pain, breathlessness, and a high prevalence of psychological health problems. These symptoms increase with the severity of CKD.

Measurement of Kidney Function

Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)

Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) is the standard measure of kidney function. Measurement of true GFR is not practical in routine clinical practice as it is time consuming and expensive. Therefore, standardised formulae have been developed to calculate estimated GFR (eGFR). These formulae incorporate serum or plasma creatinine, age and sex. eGFR is routinely calculated by all laboratories in the United Kingdom and reported alongside creatinine values.

Current NICE guidance recommends use of the 'Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) (2009)' equation for this purpose.

- NICE recommends that this equation is used without an ethnicity adjustment factor.

- The CKD-EPI 2021 equation should not be used as it has not been validated in UK populations.

There are important practical considerations in interpreting eGFR. Whilst 'normal' eGFR is defined as 90 ml/min/1.73m² or more, caution should be applied as follows:

- an eGFR of 60 to 89 ml/min/1.73m² should be classified as normal in the absence of any other evidence of CKD.

- a single eGFR of 51-59 ml/min/1.73m² in an individual who has had a previous eGFR of 60 ml/min/1.73m² or has not previously had an eGFR reported should not trigger a diagnosis of CKD without a confirmatory eGFR.

- There is biological variation in creatinine generation and clearance and laboratory variation in the performance of the creatinine assay such that a change in eGFR of up to 10% may represent variation that is not significant. Care should be taken in communicating a change in eGFR (e.g. do make statements about kidney function declining without confirmatory blood tests)

- eGFR calculations assume that the level of creatinine in the blood is stable, within biological variance, over days or longer - i.e. steady-state; the calculations are not valid if creatinine is rapidly changing, such as in acute kidney injury (AKI) or in patients receiving dialysis.

- Use change in eGFR with time (delta or slope eGFR) to confirm decline in kidney function.

- Always interpret the risk of progression of CKD by considering both the eGFR and the ACR (see below)

If a more accurate GFR is needed, for example, for chemotherapy drug dosing or in the evaluation of kidney function in potential living kidney donors, measured GFR can be undertaken using a reference standard (e.g. 51Cr-EDTA, 125I-iothalamate or iohexol).

Creatinine Clearance

In product literature for therapeutic drugs, the effects of kidney impairment on drug elimination is usually stated in terms of creatinine clearance (CrCl) as a surrogate for GFR. Although eGFR and CrCl are not interchangeable, for most drugs and for most adult patients of average build and height, eGFR (rather than CrCl) can be used to determine dosage adjustments. Exceptions to the use of eGFR include toxic drugs, older individuals, and in those with extremes of muscle mass. In addition, the Medicines Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) advises that CrCl should be used as an estimate of renal function for direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs), and drugs with a narrow therapeutic index that are mainly kidney excreted.

eGFR and ethnicity adjustment:

There is increasing concern worldwide that the previous practice of applying a fixed ethnicity adjustment when calculating eGFR for individuals of Black ethnicity is inaccurate and may lead to inequity in care. These adjustments do not reflect the wide diversity present amongst individuals from this ethnic group and were based on outdated and unfounded biological assumptions for differences, at the expense of better understanding of social and ancestral determinants of health. For this reason, in the 2021 NICE CKD guideline update, the recommendation to adjust for ethnicity (which was present in the 2014 version) was removed. The UKKA supports NICE recommendations that adjustments in eGFR for black ethnicity may not be valid or accurate and should be removed from UK practice.

Interpretation of eGFR:

eGFR is used to classify severity of kidney disease in conjunction with proteinuria/albuminuria. It is important to bear in mind the following when applying eGFR values in clinical practice:

- The equations used for eGFR tend to underestimate normal or near-normal kidney function, although the CKD-epi (2009) equation is more reliable at higher eGFR than the previous widely used 'Modification of Diet in Renal Disease' (MDRD) formula. It is advisable that slightly lower values (i.e. around or just below the 60 ml/min/1.73m CKD "cut-off" level) should not be over-interpreted. In this situation repeat testing, looking for a progressive decline in eGFR over time is useful.

- Differences in the assays used by laboratories to measure serum creatinine (NICE recommend use of the more specific enzymatic assays in preference to Jaffe colorimetric assays)*.

- Blood samples should ideally be received and processed by the laboratory within 12 hours of venepuncture, as unnecessary delays can interfere with assay results.

- Adults should be advised not to eat any meat in the 12 hours before having a blood test for eGFR, as this can affect serum creatinine concentration.

- If a sudden significant decline in kidney function is noted, this should be repeated within 2 weeks to exclude an acute kidney injury (AKI).

- The CKD-EPI equation is not validated for patients under 18 years of age or in pregnancy. There is also limited evidence regarding its accuracy in patients from different ethnic groups living in the UK.

- eGFR is only an "estimation" of true kidney function: It is important to remember that eGFR is only an estimate of true kidney function and significant error is possible, especially in people at extremes of body habitus e.g. patients with limb amputations, those who are severely malnourished, bodybuilders, oedematous or morbidly obese. For any individual patient, identifying trends in eGFR can be more informative than one-off readings.

Patient information

eGFR is an equation that uses your creatinine, age, and gender to see how well your kidneys are working. Creatinine is the level of muscle waste in your bloodstream, which your kidneys are supposed to filter out into urine.

If there is a high level of creatinine in your bloodstream, it could mean that your kidneys are not working well at filtering.

Your healthy creatinine level depends on how much muscle you have in your body and the "good" number may be different for people who have lower or higher muscle mass than average. Because the "good" creatinine number is different in everyone, eGFR is used as a more reliable measure of kidney function in stable patients than creatinine alone.

"Normal" eGFR is approximately 100 but you will often see it reported as >90 ("greater than 90") or >60 ("greater than 60"). It is for this reason that patients (and some doctors) sometimes quote the eGFR as a percentage of normal kidney function. Whilst not factually correct, it does help to make the numbers easier to understand.

Albuminuria/Proteinuria

Excessive albumin/protein excretion in the urine is a significant risk factor for both progression of CKD and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Unlike haematuria, albuminuria is almost always kidney in origin. In clinical practice albuminuria/proteinuria is usually measured as albuminuria as a test for albuminuria based on a single spot urine sample to provide a urinary albumin-to-creatinine (ACR) level. Where a urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio (PCR) is done an estimate of ACR can be provided by multiplying PCR by 0.7.

Measurement of albuminuria forms an essential part of renal function assessment:

- Urinary albumin leak may be the very first sign of kidney disease for many patients, such as those with diabetic kidney disease and may appear many years before eGFR starts to decline.

- In patients known to have CKD, quantification of albuminuria allows risk-stratification and identification of those patients who are at highest risk of progression to kidney failure (see 4 variable kidney failure risk ).

- Albuminuria is an important independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

- Measurement of ACR forms the basis of the NICE grading system for CKD - see CKD stages.

- The level of albuminuria will help determine optimum patient management e.g. frequency of monitoring, blood pressure target, eligibility for disease modifying therapies such as renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system(RAAS) inhibitors and sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, alongside timing of referral to see a specialist service (see management of CKD).

- Excessive albuminuria or the combination of haematuria and albuminuria may suggest an underlying glomerular disorder, especially in patients with other signs of auto-immune or multi-system disease. it is important that these patients are referred urgently for specialist assessment (see referral to specialist). Generally, a patient who does not have diabetes and has an ACR of 70 mg/mmol or more or haematuria (diagnosed on and confirmed by urinary diptest) and an ACR of 30 mg/mmol or more should be evaluated by a nephrologist for evidence of kidney disease.

- In patients with albuminuria the risk of kidney failure is greater in younger patients and the risk of cardiovascular disease is greater in older patients. These risks may be altered by therapy.

There is an urgent need to improve rates of urine ACR testing for patients at risk of or living with kidney disease across the UK.

How to measure albuminuria/proteinuria:

- Reagent strips are no longer recommended as screening tools for albuminuria/proteinuria. A quantitative test should be used instead.

- Urine ACR is the recommended first-line test to assess for proteinuria. It has better sensitivity at an ACR< 70mg/mmol compared to urine PCR.

- A urine ACR result between 3-70 mg/mmol should be rechecked on an early morning sample to confirm the result. Some patients may have benign orthostatic proteinuria, which can be excluded by an early morning test.

- ACR results >70 mg/mmol do not need a confirmatory repeat.

- For quantification and monitoring of higher levels of proteinuria (e.g. ACR > 70 mg/mmol) PCR is acceptable, to convert to ACR multiply by 0.7.

- A PCR of 100 mg/mmol, or ACR of 70 mg/mmol, is equal to approximately 1g of protein per 24 hr; below this level the conversion is non-linear.

Who should be tested for albuminuria/proteinuria:

- All patients with confirmed or suspected kidney disease require evaluation with a urine ACR test.

- Patients at risk of developing kidney disease require regular testing with both eGFR AND urine ACR. This includes people with:

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Previous episode of acute kidney injury

- Cardiovascular disease (ischaemic heart disease, chronic heart failure, peripheral vascular disease or cerebral vascular disease)

- Structural renal tract disease, recurrent renal calculi or prostatic hypertrophy

- Multisystem diseases with potential kidney involvement, for example, systemic lupus erythematosus

- Gout

- Family history of end-stage renal disease (GFR category G5) or hereditary kidney disease

- Incidental detection of haematuria or proteinuria.

Management of patients with proteinuria:

A number of urine ACR based treatment thresholds have been recommended by NICE.

| ACR result (mg/mmol) | NICE Guideline recommendations |

|---|---|

| ACR >3 | Abnormal and adequate to define CKD G1 or G2. Commence ACEI/ARB if patient has diabetes. For patients with T2DM, initiate SGLT2i if eGFR ≥20–25 ml/min/1.73m². |

| 22.6 | Commence SGLT2 inhibitor in patients with non-diabetic CKD and an eGFR of ≥20–25 ml/min/1.73m². |

| 30 | Favour RAAS inhibitors if hypertensive. |

| 70 | Threshold to consider RAAS inhibitor prescription and a lowered BP target of 130/80. Consider referral for specialist nephrology advice unless proteinuria known to be caused by diabetes and treatment has already been optimised. |

| >300 | Referred to as "nephrotic range" proteinuria. In the presence of oedema and hypoalbuminaemia, sufficient to define the "nephrotic syndrome". These patients must be referred to a specialist. |

Information for patients

In health only small quantities of protein are present in the urine. If higher levels of protein are present this is termed 'proteinuria'. Proteinuria can be a marker of kidney damage and patients with higher levels of protein in their urine are at increased risk of developing heart disease and progressive kidney damage. It is important to identify these individuals as they may benefit from different interventions to reduce their risk of developing heart disease or worsening kidney disease.

Click here to download our quick reference guide on albuminuria and ACR testing.

Click here to download our quick reference guide on proteinuria.

Haematuria

Visible (also known as macroscopic or frank) haematuria

Management:

- Usually, fast track Urology referral for imaging and cystoscopy unless strong pointers to acute renal disease.

Non-visible (also known as microscopic) haematuria

Detection:

- Use reagent strips rather than urine microscopy for detection. (There is no need to perform microscopy to confirm a positive result.)

- Evaluate further if there is a result of 1+ or more.

- Non-visible haematuria should be confirmed on at least 2 out of 3 consecutive urine tests (taken on separate occasions).

- Measure renal function and assess for proteinuria in all cases.

Management:

Age >60:

- Usually refer to urology (see local guidance for referral pathways). If renal impairment and/or proteinuria also present, consider simultaneous referral to nephrology.

Age <60 or >60 with negative urological investigations

- If no proteinuria AND eGFR > 60 ml/min/1.73m² manage as CKD stage G1/G2 otherwise refer to nephrology.

For further information please review the NICE guidelines.

Information for patients

Haematuria means blood in the urine. Sometimes this is visible to the naked eye or it may only detected by a urine dipstick test or when urine is examined using a microscope. Lots of different conditions can result in blood urine in the urine. The most likely cause varies depending on your age, if you are leaking protein (as well as blood) in the urine, and whether your kidney function is impaired. Further investigations may be required to find the cause.

CKD Stages

CKD Classification

A patient is said to have chronic kidney disease (CKD) if they have abnormalities of kidney function or structure present for more than 3 months.

The definition of CKD includes all individuals with markers of kidney damage (see below*) or those with an eGFR of less than 60 ml/min/1.73m² on at least 2 occasions 90 days apart (with or without markers of kidney damage).

- *Markers of kidney disease may include: albuminuria (ACR > 3 mg/mmol), haematuria (of presumed or confirmed renal origin), electrolyte abnormalities due to tubular disorders, renal histological abnormalities, structural abnormalities detected by imaging (e.g. polycystic kidneys, reflux nephropathy) or a history of kidney transplantation.

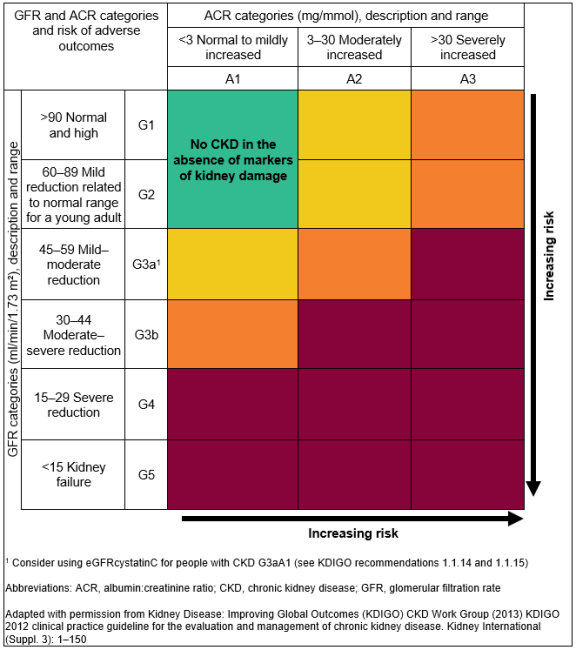

CKD Classification

CKD is classified based on the eGFR and the level of proteinuria and helps to risk stratify patients.

Patients are classified as G1-G5, based on the eGFR, and A1-A3 based on the ACR (albumin:creatinine ratio) as detailed below:

For Example

- A person with an eGFR of 25 ml/min/1.73m² and an ACR of 15 mg/mmol has CKD G4A2.

- A person with an eGFR of 50 ml/min/1.73m² and an ACR of 35 mg/mmol has CKD G3aA3.

It is important to note that patients with an eGFR of >60 ml/min/1.73m² should not be classified as having CKD unless they have other markers of kidney disease (see above*).

Patient information

Patients with CKD can be classified depending on their level of kidney function, or eGFR, and the amount of protein present in the urine. This information forms the basis of CKD staging which is useful for planning follow up and management. The higher the stage (G1->G5) and the greater the amount of protein present in the urine (A1->A3) the more "severe" the CKD and the higher the risk that a patient may develop renal failure requiring dialysis in the future.

Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE)

What is the Kidney Failure Risk Equation?

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE) is a well-validated risk prediction tool for a kidney replacement therapy (KRT) in the next two or five years in individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages 3a-5.

To estimate the risk of KRT, the four-variable KFRE uses:

- Age

- Sex

- Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)

- Urine albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR)

The KFRE has been re-calibrated specifically for the UK population and is available via this website. Please note that this may be different from some other publicly available calculators.

When should the Kidney Failure Risk Equation be calculated?

The KFRE should be calculated when an individual with CKD Stage 3a-5 has an eGFR and ACR measured. This should be at least on an annual basis, but more frequently with more advanced disease (see the frequency of monitoring section of management of patients with CKD). We would recommend that both eGFR and ACR should be within six months of each other, and ideally within a month.

How will the Kidney Failure Risk Equation improve care for my patients?

-

The UK re-calibrated KFRE has recently been recommended by NICE to guide personalised care for people with CKD stages 3a-5 including referral to secondary care. If the risk of KRT is >5% in the next 5 years, referral should be considered factoring in the patient's 'wishes and comorbidities'. This threshold has replaced the previous recommendation for considering referral if eGFR is less than 30 ml/min/1.73m². This is because it is likely to be more sensitive and specific for KRT and may reduce the number of people referred unnecessarily.

-

Two-year predictions may be more applicable to secondary care when discussing the risk of requiring KRT over a shorter timeframe and planning for procedures such as fistula formation or transplant listing.

How do I communicate Kidney Failure Risk Equation scores with patients?

Discussing KRT risk with should follow NICE's guidelines for 'shared decision making' and should include:

- Discussing KRT risk in the context of a patient's life, such as comorbidities and what matters most to the patient

- Describing KRT risk over the appropriate timeframe using 'natural frequencies' such as '10 in 100', instead of percentages such as '10%'

- Use a mixture of numbers and pictures

What are some limitations of the Kidney Failure Risk Equation?

- As KFRE uses eGFR and urine ACR to make a prediction, the same limitations for eGFR and urine ACR are also applicable to KFRE. Examples include assessment of patients at extremes of weight or muscle mass, or where a patient is being assessed in the context of acute kidney injury, or for ACR where a patient has a urinary tract infection. Please see the measurement of kidney function sections on eGFR and albuminuria for further explanation.

- KFRE should always be viewed in the context of the individual, their comorbidities, and their risk of dying from other causes over a period of the next two/five years.

- There has been limited specific validation of the KFRE in primary renal pathologies such as glomerulonephritis, cystic kidney disease and vasculitis. Therefore, in these groups caution should be used when making predictions based on KFRE.

More detailed information on KFRE including its development is available here.

CKD Stages G1 and G2

Identifying patients with CKD stages G1 & G2

An eGFR of >90 ml/min/1.73m² is considered normal kidney function. If these patients have evidence of kidney disease* however (see below) they should be classified as CKD stage G1.

Patients with an eGFR of 60-90 ml/min/1.73m² have mildly reduced kidney function which may be appropriate for their age. If these patients have any other evidence of kidney disease* (see below) they have CKD stage G2.

*Evidence of kidney disease, required to diagnose CKD in patients with an eGFR >60 ml/min/1.7m², may include:

- Proteinuria

- Haematuria (of presumed or proven renal origin)

- Structural abnormalities (e.g. reflux nephropathy, renal dysgenesis, medullary sponge kidney)

- A known diagnosis of a genetic kidney disease (e.g. polycystic kidney disease)

- Abnormalities detected by examination of renal histology

- Electrolyte abnormalities due to renal tubular disorders

- History of kidney transplantation

Initial assessment of CKD stages G1 and G2

The initial assessment for most of these patients will be undertaken in primary care settings.

The aim of the initial assessment is to determine which patients are at risk of progressive renal disease.

- All patients should have a urine specimen sent for measurement of the albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR).

- Urine reagent stick should be used to check for haematuria.

- If assessment is precipitated by a first discovery of an elevated serum creatinine level it is important to ensure that the renal function is stable. Previous blood tests, if available, will give you the answer. If no previous blood tests are available and the patient is well with no other worrying features (e.g. high potassium, symptoms of bladder outflow tract obstruction, severe hypertension), repeat the test within 14 days. Patients with deteriorating renal function require rapid assessment.

- Measure blood pressure. CKD can be a consequence of hypertension and CKD of any aetiology can be associated with hypertension. An elevated serum creatinine level may be the first clue that a patient is hypertensive.

Management of CKD stages G1 and G2

This applies to patients with stable stages G1 and G2 CKD. To diagnose CKD, two or more blood tests are required at least 90 days apart. The CKD staging and management outlined below is predicated on stable renal function.

Almost all patients with stages G1 and G2 CKD can be appropriately managed in primary care. The principal aim is to identify individuals at risk of progressive renal disease.

Some patients need further investigation where there are indications that progression to end stage renal failure (Stage G5) may be a possibility. These patients should usually be referred to the local nephrology service. Pointers to progression of renal disease include:

- Proteinuria - the risk is graded but a common cut-off for further investigation in patients without diabetes is ACR>70 mg/mmol or PCR>100 mg/mmol

- Haematuria of renal origin

- Rapidly deteriorating renal function

- Young age - the referral threshold should be much lower for younger patients in whom the lifetime risk of developing progressive kidney disease is higher.

- Family history of renal failure

- Hypertension which is difficult to control

Risk of cardiovascular events and death is substantially increased by the presence of CKD and or proteinuria and the risks of these two are additive. Patients with stages G1 and G2 CKD are much more likely to suffer a cardiovascular event than they are to require renal replacement therapy (dialysis or a transplant) in their lifetime. Patients should be offered lifestyle advice including recommendations for regular exercise, smoking cessation and attainment and maintenance of a healthy weight.

Long term monitoring of renal function, proteinuria and blood pressure should be performed for all patients. The principal aim of long term monitoring is to identify the minority of patients with stage G1 and G2 CKD who will go on to develop progressive renal disease.

- Renal function and proteinuria - patients with a urine ACR >3 mg/mmol (i.e. A2 and A3) should undergo annual monitoring of renal function and proteinuria. Patients with ACR<3 mg/mmol may be monitored less frequently (See more on stages of CKD). Patients with evidence of rapidly progressive renal impairment or who have worrying features (e.g. difficult to control hypertension, anaemia, hyperkalaemia, features of a systemic disease) should be considered for referral to renal services.

- Worsening proteinuria is an adverse prognostic sign. In patients with worsening proteinuria which exceeds ACR>70mg/mmol consider referral / discussion with nephrology unless it is known to be caused by diabetes and is appropriately treated. (See the management of patients with CKD section on Referral Guidelines).

- Blood pressure - Aim to keep the BP <140/90. In patients with CKD and diabetes or an ACR>70 mg/mmol aim to keep BP<130/80. (See the management of patients with CKD section on blood pressure (hypertension) management.)

- Cardiovascular disease - Offer advice on smoking cessation, exercise and lifestyle. (See the management of patients with CKD section on cardiovascular risk reduction.)

Patient information - CKD G1 and G2

CKD stage G1 is kidney disease with normal renal function. Patients with CKD stage G2 have mild impairment of kidney function. Most patients with CKD stages G1 and G2 just need occasional testing to ensure things are stable. A small minority of patients need further investigations to see if they have a disease which may benefit from treatment or could lead to more serious kidney damage.

CKD Stage G3

Identifying patients with CKD stage G3

Patients with CKD stage G3 (eGFR 30-59 ml/min/1.73m²) have impaired kidney function. These patients can be further subdivided based on their eGFR as follows:

- CKD stage G3a: eGFR 45-59 ml/min/1.73m²

- CKD stage G3b: eGFR 30-44 ml/min/1.73m²

Remember that eGFR is only an estimate of kidney function (more info on eGFR).

Creatinine and eGFR in an individual are usually quite stable. Deteriorating renal function needs rapid assessment. Note that the guidance on CKD staging and management outlined below are only applicable to patients with stable renal function.

Initial assessment of CKD stage G3

The initial assessment of these patients should be undertaken in the primary care setting for the majority of patients. The principal aim of the initial assessment is to identify individuals at risk of progressive renal disease.

If assessment is precipitated by a first discovery of an elevated serum creatinine level it is important to ensure that the renal function is stable. Previous blood tests, if available, will give you the answer. If no previous blood tests are available, and the patient is well with no other worrying features (e.g. high potassium, symptoms of bladder outflow tract obstruction, severe hypertension), repeat the test within 14 days. Patients with deteriorating renal function require rapid assessment.

- Clinical assessment - Consider obstruction in patients with prominent urinary tract symptoms or suggestive clinical findings (e.g. palpable bladder).

Is the patient well? Is there a history of significant associated disease? Consider referral if patient is unwell, a systemic disease process involving kidneys is suspected and / or supported by urinary abnormalities or other indicators.

- Medication review - are there any potentially nephrotoxic drugs or drugs that need dose alterations in patients with renal impairment? Remember non-prescribed and over the counter medications, e.g. NSAIDs.

- Urine tests: dipstick for blood and quantitation of proteinuria by ACR. Presence of haematuria or proteinuria may suggest intrinsic renal disease.

- Think if the CKD could be a complication of an existing diagnosis or a presenting feature of a new diagnosis e.g. diabetes, hypertension, multiple myeloma, connective tissue disease.

- Is there a family history of CKD or renal failure? May suggest a heritable disease, such as ADPKD, Alport's syndrome, reflux nephropathy.

- Imaging - exclusion of obstruction is indicated in patients with significant urinary symptoms or in whom there is a clinical suspicion of obstruction. An ultrasound scan of the renal tract is the usual screening investigation in this setting.

Management of CKD stage G3

This applies to patients with stable CKD stage G3.

Some patients need further investigation where there are indications that progression to end stage renal failure (Stage G5) may be a possibility. These patients should usually be referred to the local nephrology service. Pointers to progression of renal disease include:

- Proteinuria - the risk is graded but a common cut-off for investigation in patients without diabetes is ACR>70 mg/mmol or PCR>100 mg/mmol

- Haematuria of renal origin

- Rapidly deteriorating renal function

- Young age - the referral threshold should be much lower for younger patients in whom the lifetime risk of developing progressive kidney disease is higher.

- Family history of renal failure

- Hypertension which is difficult to control (on more than 4 agents)

Risk of cardiovascular events and death is substantially increased by the presence of CKD and or proteinuria and the risks of these two are additive. Patients with CKD stage G3 are, on average, more likely to suffer a cardiovascular event than they are to require renal replacement therapy (dialysis or a transplant) in their lifetime. Patients should be offered lifestyle advice including recommendations for regular exercise, smoking cessation and attainment and maintenance of a healthy weight. Offer patients with CKD stage 3-5 Atorvastatin 20 mg for the primary and prevention of cardiovascular disease and manage patients for secondary prevention as recommended by NICE.

Long term monitoring of renal function, proteinuria and blood pressure should be performed for all patients. The aims of monitoring are to identify the minority of patients with CKD stage G3 who will progress to end stage renal failure and to identify complications of CKD.

- Renal function should be monitored at least annually. For patients with significant proteinuria (i.e. A3) the renal function should be checked at least twice yearly. Consider referring patients to nephrology with rapidly declining renal function, i.e. a sustained decrease in GFR of 25% or more and a change in GFR category, or a sustained decrease in GFR of 15 ml/min/1.73m² or more within 12 months.

- Proteinuria - monitor with serial ACR or PCR. Note the suggested thresholds of ACR>70 (or PCR>100) mg/mmol for more stringent blood pressure targets and ACR>70 (or PCR>100) mg/mmol or ACR >30 (or PCR >50) mg/mmol with haematuria for specialist referral/discussion (see more on proteinuria in the measurement of kidney function section). Patients with diabetes and ACR>3 mg/mmol should be prescribed maximal tolerated dose of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (RAASi) and sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i). For non-diabetic patients with ACR>22.5 mg/mmol a SGLT2i should be considered. For non-diabetic patients with hypertension and ACR > 30 mg/mmol or ACR>70 mg/mmol (regardless of blood pressure) RAASi should be considered. (see more on RAASi and SGLT2i in the management of patients with CKD section).

- The 4 variable Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE) should be used to calculate patient risk of progression to renal failure using age, sex, eGFR and urine ACR values every time renal function monitoring is undertaken. A 5-year risk of kidney failure >5% should prompt referral to a nephrology specialist. (see more on KFRE in the CKD stages section)

- Blood pressure - Aim to keep the BP <140/90. In patients with CKD and diabetes or an ACR>70 mg/mmol aim to keep BP<130/80 (see more on hypertension and blood pressure in the management of patients with CKD section).

- Cardiovascular risk - offer advice on smoking, exercise and lifestyle. Consider offering Atorvastatin 20 mg nocte for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (see more on cardiovascular risk reduction in the management of patients with CKD section).

- Haemoglobin - if low, first exclude "non-renal" aetiologies. Haemoglobin levels fall progressively commensurate with deteriorating renal function although significant anaemia attributable to CKD is rare before CKD stage G3b or G4. For patients with haemoglobin levels approaching or below 100 g/L specific interventions may be considered. (see more on anaemia in the complications of advanced CKD section).

- Immunisation - influenza and pneumococcal vaccination should be offered. Currently patients with CKD 3 are also being offered seasonal COVID boosters (subject to change)

- Medication review - regular review of medication to minimise nephrotoxic drugs (particularly NSAIDs) and ensure doses of others are appropriate to renal function.

Patient information

Patients with CKD stage G3 have impaired kidney function. Only a minority of patients with CKD stage G3 go on to develop more serious kidney disease. Cardiovascular disease, the umbrella term for diseases of the heart and circulation (e.g. heart attacks and strokes), is more common in patients with CKD. It is important to try and identify which patients may go on to develop more serious kidney damage and to try and reduce the chances of patients developing serious complications. It is important that blood tests are monitored regularly (6-12 monthly) to look for any significant decline. In addition to this it is essential that the level of protein in your urine (ACR) is also checked regularly, this can help us determine your risk (see kidney failure risk equation) and also your eligibility for important therapies that can reduce the likelihood of you developing serious kidney or heart disease.

Cardiovascular risk reduction

CKD significantly increases the risks of both fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events. At the population level these increased risks can be observed even in patients with low levels of proteinuria and preserved renal function. The risks increase with declining renal function and worsening proteinuria. Standard cardiovascular risk prediction tools, such as Framingham tables and Qrisk scores, significantly underestimate the risks of cardiovascular disease in patients with CKD.

These observations reinforce the importance of trying to control the modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in patients with CKD. Such approaches may include:

General measures

- Smoking cessation

- Weight loss

- Regular aerobic exercise

- Limiting salt intake

Control of hypertension

- To a maximum of 140/90 or 130/80 according to absence/presence of proteinuria or diabetes (see the blood pressure (hypertension) management section)

Lipid lowering therapies

- Offer Atorvastatin 20 mg for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in all patients with CKD, irrespective of their serum lipid levels.

- Increase the dose if there is <40% reduction in non-HDL cholesterol and eGFR is > 30 ml/min/1.73m², particularly for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Prescription of anti-proteinuric drugs

Both RAS inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors in eligible patients have been shown to reduce patient risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events.

Information for patients

Patients with CKD are more likely to develop heart disease or other diseases of the blood vessels such as strokes than they are kidney failure. A number of things can be done to minimise these risks including lifestyle changes and medications.

Assessment of patients with a new diagnosis of CKD

Aetiology

Some of the leading causes of CKD in the UK include:

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Renovascular disease

- Inherited renal diseases

- Glomerulonephritis

- Reflux nephropathy

- Heart Failure (cardio-renal syndrome)

History taking, examination and investigations may help identify the likely aetiology of CKD in individual cases but where the diagnosis remains uncertain, especially in those patients with a progressive decline in renal impairment consider referral to your local nephrology unit (see referral criteria in the management of patients with CKD section).

History Taking

A good history may help establish the likely aetiology of CKD. The leading causes of CKD in the UK are currently diabetes and hypertension. History taking should clarify not only the presence of these risk factors but should focus on establishing the likelihood that they have contributed to development of CKD. This will include questions about the duration of disease and how good historic glycaemic and blood pressure control has been. Especially in diabetic patients, nephropathy is more likely when other microvascular complications of disease are present; a history of retinopathy (especially proliferative diabetic retinopathy requiring laser treatment) or peripheral neuropathy and diabetic foot disease should be explored.

Other common causes of CKD include renovascular disease, which may be suspected in patient known to have peripheral vascular disease, reflux nephropathy which frequently occurs in patients with a history of recurrent childhood urinary tract infections (UTIs) and enuresis and cardio-renal syndrome observed in patients with moderate/severe or decompensated heart failure. Chronic glomerulonephritis may be suggested in patients with a history of auto-immune disease or evidence of multi system involvement e.g. rash, joint swelling, uveitis, respiratory symptoms or fever. Myeloma is an important but under-recognised cause of renal impairment, especially in the elderly and a history of back pain may be suggestive. Prostatic symptoms in males such as poor stream, nocturia and a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying may raise suspicion of bladder outflow tract obstruction. In males, bladder cancer, and in females, a past history of gynecological malignancy, pelvic surgery, or radiotherapy are additional important risk factors for potential ureteric obstruction.

Medications are commonly implicated in development of renal impairment and a detailed drug history is essential e.g. NSAIDs and lithium use. Drug history should also include questions around the use of any over the counter or herbal treatments and history of illicit substance abuse.

It is important to identify any family history of kidney disease. In cases of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, it is also helpful to know details of disease presentation and progression in relatives and whether anyone is known to have had an intracerebral haemorrhage or sudden death, as the clinical phenotype of disease can vary. If the exact nature of familial kidney disease is unknown the pattern of inheritance may give some clues e.g. X-linked inheritance is seen in Alport syndrome.

The history may also seek to explore any complications of CKD, but it is important to note that the vast majority of patients will be asymptomatic until they develop very advanced renal impairment or uraemia, typically around CKD stage 5 (eGFR<15 mLs/min). Symptoms associated with advanced CKD may include:

- fatigue

- nausea and vomiting

- leg swelling

- breathlessness on exertion

- loss of appetite, loss of weight

- itching

- 'restless legs' syndrome

- Insomnia

- nocturia and polyuria

- bone pain

- peripheral oedema

- symptoms due to anaemia

- amenorrhoea in women

- erectile dysfunction in men.

Examination

When trying to determine the aetiology of CKD, the examination may provide a number of clues:

- Diabetes - Presence of other systemic microvascular complications will increase suspicion of diabetic kidney disease (diabetic nephropathy). Ophthalmoscopy is helpful to identify features of proliferative retinopathy or previous laser treatment. Neurological examination of the foot (typically with a monofilament) can help identify peripheral neuropathy as can evidence of neuropathic foot ulcers, previous lower limb amputation or Charcot foot.

- Hypertension - Blood pressure examination is essential in all patients with kidney disease, it is not only important to help identify the aetiology but is a critical component of patient management. Good blood pressure control can reduce the risk of CKD progression and cardiovascular complications. In patients with advanced CKD volume overload can lead to oedema and hypertension. Ophthalmoscopy can be used to identify evidence of hypertensive changes in the retina, such as silver wiring, arteriovenous nipping and retinal haemorrhages which can be indicative of suboptimal control, at least historically, and increase the likelihood of hypertensive nephropathy.

- Fluid balance - Patients with advanced CKD or underlying nephrotic syndrome may develop significant peripheral oedema. Those with decompensated heart failure at risk of cardio-renal syndrome may also present with significant fluid overload.

- Renovascular disease - Renal bruits may be heard. The presence of femoral bruits and weak or absent peripheral pulses indicates significant peripheral vascular disease, which increases the likelihood of associated renovascular disease.

- Inherited kidney diseases - Polycystic kidneys are often palpable and some patients may also have hepatomegaly due to liver cysts. Patients with Alport's syndrome may require hearing aids for sensorineural hearing loss caused by abnormal collagen IV in the basement membrane of the inner ear.

- Glomerulonephritis - rash, fever, murmur, red eye and joint swelling may point to an underlying multi-system disorder. Significant peripheral oedema may be noted in patients with nephrotic syndrome. Pleural effusions and ascites may also be present.

- Obstructive uropathy - A palpable enlarged bladder is suggestive of outflow tract obstruction. This may be painless if it has developed insidiously over a prolonged period of time. Patients with a hydronephrotic kidney may occasionally complain of loin pain.

Investigations

- eGFR - Any acute decline in eGFR should be repeated within 14 days to exclude an acute kidney injury (AKI) which requires urgent assessment. (See eGFR) (See CKD staging) (see deteriorating renal function).

- Proteinuria - Urine ACR is the first line investigation for proteinuria. It is an essential component of renal function assessment. (see proteinuria).

- Haematuria - haematuria seen in association with proteinuria may be suggestive of an underlying glomerulonephritis.

- Full blood count and iron levels - patients with advanced CKD may develop anaemia of chronic disease (see anaemia). Anaemia may also be observed in those with suspected myeloma.

- Bone Profile (including phosphate and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels - Patients with advanced CKD may develop elevated phosphate levels and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Hypercalcaemia may suggest underlying malignancy (especially myeloma) and can adversely impact on renal function.

- Bicarbonate - acidosis is common in advanced CKD.

- Immunoglobulins and Serum Free Light Chains - these may be elevated in patients who have myeloma.

- Auto-immune screen - In patients with suspected glomerulonephritis, a soluble immunology screen should be sent. Typically, this will include ANA, ANCA, DsDNA and complements.

- Virology - HIV, Hep B and Hep C screening should be undertaken due to their associations with development of renal disease.

Ultrasound scan

A renal tract ultrasound should be requested in the following patients with CKD.

- When there is accelerated progression of CKD (defined as sustained decrease in eGFR of 25% or more and a change in GFR category within 12 months or a sustained decrease in GFR of 15 ml/min/1.73m² per year)

- Patients with visible or persistent invisible haematuria

- Patients with symptoms of urinary tract obstruction

- If there is a family history of polycystic kidney disease and patient is older than 20 years of age.

- Patients with an eGFR of less than 30 ml/min/1.73m²

- Patients considered by a nephrologist to need a renal biopsy.

Kidney Biopsy

Indications and suitability for a kidney biopsy will be reviewed by a specialist. Percutaneous kidney biopsy remains the gold standard investigation for diagnosis of intrinsic renal disease. Indications include unexplained renal impairment, especially when disease is progressive, to try and identify potentially treatable causes. For patients who present with suspected glomerular disease or interstitial nephritis, a biopsy is important to confirm the diagnosis and inform clinical decision making. The kidney biopsy can also play an important role in prognostication e.g. by quantification of the extent of chronic tissue damage, when risks associated with some treatment may outweigh potential benefit.

Undergoing a kidney biopsy is not without risk however, including a small but significant risk of bleeding which may be life-threatening in rare cases. For this reason, a decision to undertake a kidney biopsy should be carefully considered by clinicians and patients counselled appropriately, especially for those at highest risk (single kidney, uncontrolled hypertension, small kidneys, blood clotting disorders, obesity, frailty and confusion that may impact on a patient's ability to comply with instructions).

Management of patients with CKD

Coding of CKD in primary care

All patients with CKD should be coded in their primary care electronic health records. This should preferably use the complete CKD classification system, which is regularly updated to reflect the most recent eGFR and uACR result (see diagnosis of CKD) (see CKD staging). Improved coding of patients with CKD should support pathways that ensure regular review and monitoring of patients on the CKD register and may also enhance safe prescribing through automated decision support alerts.

A new diagnosis of CKD should always be discussed with the patient (and/or their carers), taking into account the severity of the condition, likely cause and associated risk. Ideally, this discussion should be supported by high quality patient information resources, tailored to patient needs.

Frequency of monitoring

The recommended minimum frequency of monitoring for patients with or at risk of CKD is set out in the most recent NICE guidance as below (Table). This may be tailored to individual patients depending on some of the following factors:

- The underlying cause of CKD

- The rate of decline in eGFR or increase in ACR (but be aware that CKD progression is often non-linear)

- Other risk factors, including heart failure, diabetes and hypertension

- Changes to treatment (such as RAASi, NSAIDs and diuretics)

- Intercurrent illness (for example acute kidney injury)

- Whether they have chosen conservative management of CKD.

Table: Minimum number of monitoring checks (eGFRcreatinine) per year for adults, children and young people with or at risk of chronic kidney disease

| ACR category A1: normal to mildly increased (less than 3 mg/mmol) | ACR category A2: moderately increased (3 to 30 mg/mmol) | ACR category A3: severely increased (over 30 mg/mmol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFR category G1: normal and high (90 ml/min/1.73m² or over) | 0 to 1 | 1 | 1 or more |

| GFR category G2: mild reduction related to normal range for a young adult (60 to 89 ml/min/1.73m²) | 0 to 1 | 1 | 1 or more |

| GFR category G3a: mild to moderate reduction (45 to 59 ml/min/1.73m²) | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| GFR category G3b: moderate to severe reduction (30 to 44 ml/min/1.73m²) | 1 to 2 | 2 | 2 or more |

| GFR category G4: severe reduction (15 to 29 ml/min/1.73m²) | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| GFR category G5: kidney failure (under 15 ml/min/1.73m²) | 4 | 4 or more | 4 or more |

A CKD review should include assessment of:

- Trends in eGFR decline (see deteriorating renal function)

- Level of proteinuria (see proteinuria)

- Kidney failure risk equation (see KFRE)

- Blood pressure (see BP management)

- Optimisation of glycaemic control for patients with diabetic kidney disease

- Suitability for RAS inhibitors (see RAS inhibitors)

- Suitability for SGLT-2 inhibitor (see SGLT-2 inhibitor)

- Suitability for Finerenone (see Non-steroidal mineralocortoid antagonists)

- Cardiovascular risk assessment and prescription of lipid lowering therapy (see cardiovascular risk reduction)

- Patient Education

Blood Pressure (Hypertension) Management

Multiple trials have shown the benefits of blood pressure control in patients with renal disease. These benefits include slowing the progression of CKD and reducing cardiovascular outcomes and mortality.

Patients with diabetic kidney disease or significant proteinuria (ACR>30 mg/mmol) particularly benefit from pharmacological blockade of the renin-angiotensin system with ACE (angiotensin converting enzyme) inhibitors or ARBs (angiotensin receptor blockers) to control their blood pressure (see the RAS inhibitor section).

Targets

These apply to all stages of CKD.

- ACR<70 mg/mmol or PCR<100 mg/mmol: Target blood pressure <140/90

- ACR>70 mg/mmol or PCR>100 mg/mmol OR CKD and diabetes: Target blood pressure <130/80

Referral criteria

Patients with poorly controlled BP despite the use of 4 agents should be referred to a specialist for further evaluation (see the referral to specialists section)

Dietary advice

All patients with CKD should be advised to minimise dietary salt. This will improve blood pressure control, fluid retention and can also slow down progression of their CKD.

Renin-angiotensin- system (RAS) inhibitors

RAS inhibitors include ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

Consider ACE inhibitors or ARBs in all patients with CKD and:

- Urinary ACR>70 mg/mmol (non-diabetics)

- Urine ACR>30 mg/mmol and hypertension (non-diabetics)

- Diabetes and ACR>3 mg/mmol

Exercise caution with, and potentially avoid the use of, RAS inhibitors in the following situations:

- Patients with pre-treatment potassium of >5 mmol/L

- Previous deterioration in renal function with these agents

- Known renovascular disease (this is not an absolute contraindication)

- Patients at high risk of pre-renal AKI (e.g. high output stomas, poor oral fluid intake)

- Patients co-prescribed NSAIDs

Starting and monitoring therapy with ACE inhibitors or ARBs

NICE guidance recommendation is to check serum creatinine and potassium:

- Before starting therapy

- 1-2 weeks after initiation or dose increment

For patients with an eGFR of 30 ml/min/1.73m² or more and a normal potassium it is unclear if the risk of structured retesting and the delayed optimisation of therapy outweighs the optimisation of therapy.

The practice of the authors with patients who have a potassium of 5 mmol/l or more and where an ACE inhibitor or ARB is clearly indicated is to ensure that the patients are fully counselled about hyperkalaemia and dietary information is provided and other therapy options discussed (e.g. potassium binding resins, commencing SGLT2i).

If creatinine rises >30% or GFR fall >25% repeat tests, stop drug and consider other causes e.g. volume depletion, NSAID use. If no other explanation, consider investigations for renal artery stenosis.

If creatinine rises by <30% or eGFR falls by <25% (creatinine) repeat tests in further 1-2 weeks, then action as above if criteria for drug cessation are met. Do not routinely stop or modify the RAS inhibitor if lesser changes in renal function are observed – provided any lesser rises are stable.

If K is 6-6.4 mmol/l in a patient on a RAS inhibitor consider repeating to ensure not spurious (e.g. delayed separation), stop drugs that may be contributing, (e.g. NSAIDs, potassium-retaining diuretics, trimethoprim) and enquire about diet (especially ‘LoSalt’ which is potassium chloride). If potassium is

Modest stable hyperkalaemia (5.5-5.9 mmol/l) may be preferable to discontinuing a valuable therapy. This situation is most frequently encountered in patients with diabetes and those with heart failure in whom high potassium levels are a more frequent finding and the evidence base in favour of RAAS blockade is very strong. There are a number of strategies which may be employed to lower potassium in patients with a potassium of 6-6.4 mmol/l to facilitate the continued prescription of the RAS inhibition where there is a strong clinical indication. In selected patients such strategies may include dietary potassium restriction, the addition of sodium bicarbonate, a diuretic, and/or introduction of potassium binders. Please see UKKA hyperkalaemia clinical practice guidelines for further information.

The evidence for stopping ACE inhibitors or ARBs at times of high risk for acute kidney injury is not clear and the decision should be individualised based on considerations such as the haemodynamic status. For patients with progressive CKD the evidence indicates that ACE inhibitor or ARB should be continued until kidney replacement therapy is commenced.

Dual prescription of ACE inhibitors and ARBs should not be offered. Please see MHRA guidance on this topic.

Information for patients

Blood pressure control is critically important in preventing further kidney deterioration in many patients with CKD and for protecting against damage to heart and arteries. Some of the drugs used can affect kidney function and additional monitoring may be required.

Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors

Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors were initially developed to treat hyperglycaemia in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). Results from large placebo-controlled clinical outcome trials have shifted the focus to SGLT-2 inhibition's potential to manage cardio-renal risk rather than hyperglycaemia. In people with type 2 DM at high risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, SGLT-2 inhibition reduces cardiovascular risk, particularly from heart failure.

In people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), the CREDENCE, DAPA-CKD and EMPA-KIDNEY trials have demonstrated SGLT-2 inhibition's particular efficacy at also reducing risk of kidney disease progression in people with type 2 DM as well as in patients with albuminuric CKD due to other causes. In patients with CKD SGLT-2 inhibitors have additionally been shown to reduce risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events, hospitalisations with heart failure and all-cause mortality.

The effectiveness of SGLT-2 inhibitors at glucose lowering diminishes as the kidney function falls; however, the relative effects of SGLT-2 inhibition on kidney disease progression and cardiovascular risk appear preserved in people with type 2 DM and CKD, at least within the range of kidney function represented in the reported trials (down to eGFR 15 mLs/min).

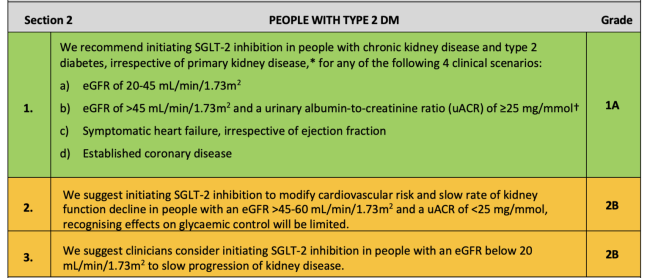

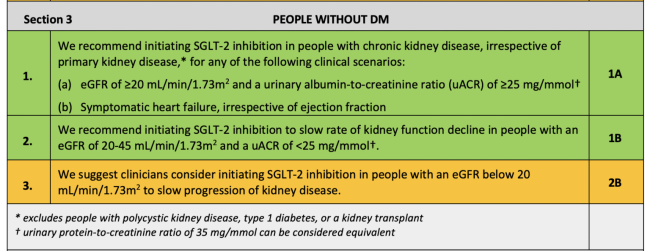

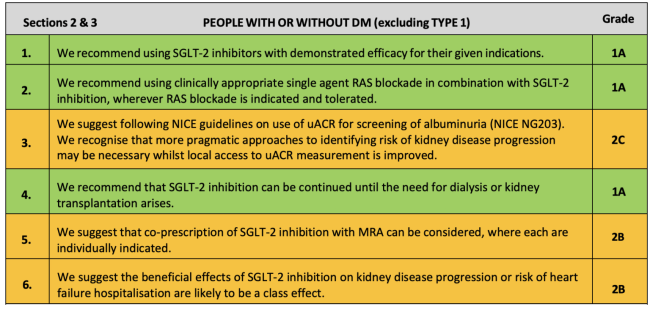

Recommendations for starting SGLT2 inhibitors

The UK Kidney Association Clinical Practice Guideline: Sodium-Glucose Co-transporter-2 (SGLT-2) Inhibition in Adults with Kidney Disease includes the following recommendations and suggestions for when to start SGLT2 inhibitors in people with CKD:♦

For people with type 2 DM:

For people without DM:

For people with or without DM (excluding Type 1):

♦ Key:Green: Recommendations with Grade 1 evidence (“we recommend” statements); Yellow: Recommendations with Grade 2 evidence (“we suggest” statements). Further details on grading can be found in Section 1, Table 1.2 of the UK Kidney Association Clinical Practice Guideline: Sodium-Glucose Co-transporter-2 (SGLT-2) Inhibition in Adults with Kidney Disease.

For more information, click here for the UKKA clinical practice guidelines on SGLT2 inhibitors.

Non-steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonists

Finerenone is a selective non-steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonist that has been shown to reduce the risk of progressive CKD in patients with diabetic kidney disease. It is recommended by NICE as add on therapy to current standard of care (RAS inhibitors and SGLT-2 inhibitors) for patients with diabetes, albuminuria and CKD stages 3 and 4 (down to eGFR 25 mLs/min). It is important to monitor for hyperkalaemia whilst on this treatment. Please see further guidance on this topic from the in the UKKA and Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) consensus statement.

Cardiovascular risk reduction

CKD significantly increases the risks of both fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events. At the population level these increased risks can be observed even in patients with low levels of proteinuria and preserved renal function. The risks increase with declining renal function and worsening proteinuria. Standard cardiovascular risk prediction tools, such as Framingham tables and Qrisk scores, significantly underestimate the risks of cardiovascular disease in patients with CKD.

These observations reinforce the importance of trying to control the modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in patients with CKD. Such approaches may include:

General measures

- Smoking cessation

- Weight loss

- Regular aerobic exercise

- Limiting salt intake

Control of hypertension

- To a maximum of 140/90 or 130/80 according to absence/presence of proteinuria or diabetes (see the blood pressure (hypertension) management section)

Lipid lowering therapies

- Offer Atorvastatin 20 mg for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in all patients with CKD, irrespective of their serum lipid levels.

- Increase the dose if there is <40% reduction in non-HDL cholesterol and eGFR is > 30 ml/min/1.73m², particularly for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Prescription of anti-proteinuric drugs

Both RAS inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors in eligible patients have been shown to reduce patient risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events.

Information for patients

Patients with CKD are more likely to develop heart disease or other diseases of the blood vessels such as strokes than they are kidney failure. A number of things can be done to minimise these risks including lifestyle changes and medications.

Deteriorating renal function

If a patient is newly discovered to have a high creatinine it is important to establish if it represents acute kidney injury (AKI) or CKD. A patient cannot be labelled as having CKD unless you know that the renal function is stable or in steady state. On finding an elevated serum creatinine in the absence of previous creatinine results, assuming the patient is well and there are no worrying clinical or biochemical features (especially potassium), recheck the serum creatinine within 7-14 days to determine the rate of change.

Acute kidney injury - Management of AKI is outside the scope of this guideline but declining renal function over hours to days needs urgent assessment. Sometimes the cause is immediately apparent (e.g. bladder outflow obstruction or drugs) and quickly remediable. If not, urgent hospital assessment is almost always required. Refer to the UKKA AKI clinical practice guidelines for further information.

Once a patient has been identified as having CKD it is important to determine the rate of progression. To determine the rate of progression, obtain a minimum of 3 GFR estimations over a period of not less than 90 days.

Consider referral to renal services if patients have rapidly progressive CKD as these patients are at increased risk of progression to end-stage kidney disease. NICE defines accelerated CKD progression as:

- A sustained decrease in GFR of 25% or more AND a change in GFR category (i.e. CKD "G" stage) within 12 months

OR

- A sustained decrease in GFR of ≤ 15 ml/min/1.73m² within 12 months

Slower rates of CKD deterioration may need specialist assessment, particularly if:

- 5-year KFRE >5% (see KFRE)

- High levels of proteinuria (ACR >70 mg/mmol in non-diabetic patients)

- Diagnostic uncertainty regarding the aetiology of the CKD

- There are symptoms suggestive of systemic disease

- Associated biochemical abnormalities, e.g. hyperkalaemia, hypocalcaemia

- Progressive anaemia

- Worsening fluid overload

Information for patients

Most patients who are newly discovered to have poor kidney function have an old problem which is changing slowly. It is important to identify those patients whose kidney function is changing more quickly. In many cases, changes to the medicines or other simple changes will be enough to put things right, although some patients may need further investigations and specialist treatment.

Referral to a specialist

Referral to a specialist should be considered and discussed with patients, taking into account their frailty and wishes for the following group of patients:

- a 5-year risk of needing renal replacement therapy of greater than 5% (measured using the 4-variable Kidney Failure Risk Equation) (see KFRE)

- an ACR of 70 mg/mmol or more, unless known to be caused by diabetes and already appropriately treated

- an ACR of more than 30 mg/mmol (ACR category A3), together with haematuria

- a sustained decrease in eGFR of 25% or more and a change in eGFR category within 12 months

- a sustained decrease in eGFR of 15 ml/min/1.73m² or more per year

- hypertension that remains poorly controlled (above the person's individual target) despite the use of at least 4 antihypertensive medicines at therapeutic doses

- known or suspected rare or genetic causes of CKD

- suspected renal artery stenosis

Complications of advanced CKD

Anaemia

Anaemia becomes more prevalent as renal function declines. Severe anaemia (e.g. Hb < 100 g/L) due to CKD is uncommon before at least CKD stage G3b. Other causes of a low haemoglobin should always be considered. The management of "renal anaemia" usually consists of erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESAs - usually based on erythropoietin) and / or iron supplementation. Treating anaemia in patients with CKD has been shown to improve quality of life.

Investigation and management of anaemia in CKD

- Exclude other causes of anaemia.

- When Hb falls below 100-110g/L treatment with intravenous iron ± erythropoiesis stimulating agents may be considered.

- The aim of treatment is to maintain Hb levels in the range 100-120 g/L. (i.e. not to 'normalise' the haemoglobin level).

Useful tips

- Haemoglobin levels both above and below the recommended target range of 100-120 g/L have been associated with adverse patient outcomes in CKD patients receiving ESAs.

- Although iron supplementation is used in the management of "renal anaemia", absolute iron deficiency is NOT a complication of CKD and should be investigated appropriately. (CKD is associated with relative iron deficiency as a result of impaired iron utilisation.)

- The tempo of change in the renal function and haemoglobin level in an individual patient can give useful pointers as to whether the anaemia is likely to be due to the CKD. i.e. stable mild CKD for several years is unlikely to be the cause of a new, progressive anaemia.

- Anaemia due to renal impairment is normally an isolated normocytic anaemia. In patients with anaemia and a macro- or micro-cytosis and / or abnormal levels of white cells or platelets consider other causes.

- Following commencement on an ESA it typically takes 2-3 months to achieve a "steady state" haemoglobin concentration therefore frequent ESA dose adjustments should be avoided.

- Failure to respond to ESA/iron therapy or increased ESA/iron requirements in a patient with stable CKD should prompt re-assessment. Common explanations for this scenario include occult bleeding (especially from the GI tract), ESA non-administration (often withheld on the basis of high blood pressure) or inter-current inflammatory illness (usually infection which blunts the erythropoietic response to ESA-administration).

There are likely to be local algorithms and protocols for management of renal anaemia.

Information for patients

Anaemia (low haemoglobin concentration), is frequently encountered in patients with CKD. It becomes more common with lower kidney function declines. Treatment of the anaemia, once the cause has been established, usually consists of giving patients iron (either in tablet or liquid form to swallow or as an infusion through a drip) and or injections treatment (given weekly to monthly) of a medication known as an ESA or a tablet, usually given three times a week called a HIF inhibitor. With both of these treatments ongoing monitoring is required, and dose adjustments are common.

Click here to download our Clinical Practice Guideline: Anaemia of Chronic Kidney Disease.

Click here to download our quick reference guide on anaemia of CKD.

Mineral Bone Disorder (Ca-PO4-PTH)

Disturbances of calcium and phosphate metabolism arise in moderate to severe CKD (i.e. usually CKD stages G4 and G5). The umbrella term for these abnormalities is CKD-Mineral Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). CKD-MBD is considered a systemic disorder which is strongly linked to cardiovascular disease and mortality. The key drivers of CKD-MBD are phosphate retention (due to reduced renal clearance), disordered Vitamin D metabolism and consequent secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Detailed guidance on the management of CKD-MBD can be found in the UKKA Commentary on the KDIGO Guideline on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention and Treatment of CKD-MBD

The key principles of management comprise:

- Maintaining phosphate levels towards the normal range

- Avoiding calcium containing phosphate binders

- Phosphate binders (to minimise dietary phosphate absorption)

- Vitamin D supplementation

The goals of therapy in terms of target calcium, phosphate and PTH concentrations, vary with CKD stage. Many renal units have local protocols for the management of CKD-MBD.

Information for patients

Chronic kidney disease affects the body's ability to handle calcium and phosphate. This, in turn, can lead to problems with your heart, blood vessels and bones. There are a number of different treatment approaches which vary between patients. Options available for treatment include advice on altering your diet, a variety of tablets and, in certain cases, surgery.

See the KFRE information in the CKD stages section for more information.

Advanced kidney care (AKC, previously known as low clearance)

Advanced Kidney Care refers to the multi-professional framework required to support high quality care in patients who are at high risk of progressing to kidney failure requiring kidney replacement therapy or supportive care.

The specific criteria for AKC are developing, Renal GIRFT recommends that patients should be seen for AKC by the time that they are within 18 months of a projected requirement for kidney replacement therapy.

This section represents the approach taken by one of the authors (PC), who leads a large AKC service.

Different services use different thresholds for entering AKC. It is our practice to ensure patients should be are offered AKC by a KFRE of 20% at 2-years. KFRE does not censor for death and is not normally distributed therefore this is a level of risk that is consistent with Renal GIRFT recommendations.

There is then increasing consensus that by a KFRE of 40% at 2-years patients should have been supported to make a decision around modality choice, and this should be actioned.

The following principles are useful for AKC

Patient-reported and clinical outcomes show kidney transplantation represents the best modality for patients who are fit to receive a kidney transplant.

Kidney transplantation should be discussed with patients such that there is a documented decision around kidney transplantation. Listing at a KFRE of 40% or more is consistent will give a patient an opportunity of a pre-emptive kidney transplant. It is crucial that all patients who may be fit for a kidney transplantation are provided with support.

For patients who are not medically fit for kidney transplantation consider how risk is explained in a way that supports the patient understanding. Many patients who are unfit for kidney transplantation have a good quality of life and good long-term outcomes on dialysis.

Ensure transplant status and modality choice have been actioned by a KFRE of 40%

Patients can be discussed as indicated as active on the kidney transplant waiting list or Deferred In kidney transplant assessment clinic. If patient is not medically fit for a transplant or does not wish to proceed for a transplant, then state this in the modality list.

Home therapies (designated as continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) or Home Haemodialysis (HHD)) may be associated with better patient outcomes than in centre haemodialysis. It is uncertain as to whether CAPD or HHD is associated with better clinical outcomes, but at minimum there is clinical equipoise.

At a KFRE 40% or more patients who have chosen CAPD as a preferred modality should have been reviewed in a CAPD surgical assessment clinic or, if KFRE 40%+ and AVF done or patient listed for AVF if not done.

Supportive care pathway patients can be offered follow-up in a supportive care AKC clinic or offered discharge to primary care with a tailored management strategy.

At a KFRE of 20-39% the patient is receiving education from the AKC team to support modality choice. That choice may have been made and the patient may have been seen in the relevant service (e.g. fistula fast/transplant assessment) but suspended on the kidney transplant list.

Key clinical points for patient review

Focus on patient symptoms. For patients requiring AKC the commonest symptoms are fatigue (70%), pain, particularly bone and joint pain (60%), poor sleep, itching, cramps, sexual dysfunction (50%), psychological health symptoms are very common. Malnutrition affects 30-50% of patients.

eGFR is not a good surrogate for patients with advanced CKD. Support patients to understand this and not to over-focus on eGFR but on how they feel.

Don't express eGFR as a percentage (%).

Continue to focus on CVD risk; statin for primary prevention; RASi to continue; SGLT2i to continue; BP target to <140/80 (individualise).

Advise on reduction in salt and processed foods; this supports blood pressure control, heart disease, phosphate management and oedema management. For more information, see 'A healthy diet and lifestyle for your kidneys' (Kidney Care UK).

Manage congestion (oedema); support patients to self-manage, enable them to adjust diuretic dose using daily weights and assessment of oedema. Diuretics are not directly nephrotoxic.

Hb target is 105-125 g/L. There is a SOP for anaemia and the renal anaemia team manage this through the AKC MDT.

Bone chemistry evidence is not strong, avoid activated vitamin D (alfacalcidol or calcitriol) unless severe and progressive SHPT, nutritional vitamin D can be used. Avoid calcium containing binders unless hypocalcaemic. Vitamin D levels should be checked yearly and nutritionally supplemented if deficient. Advise on limiting processed foods and avoid calcium containing binders unless hypocalcaemic or conservative management. Hyperphosphataemia may indicate that RRT is imminent.

Bicarbonate, the evidence is conflicting; BICARB (UK RCT) showed no benefit and increased adverse events; Cochrane review was low certainty evidence; animal evidence suggests delayed progression; have an informed discussion and don't be didactic, remember pill burden.