Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)

AKI was universally called acute renal failure (ARF) until new approaches to its definition and classification emerged in the early 2000s.

Influential observations about the course and cause of ARF were made during World War 2 at Hammersmith Hospital. Eric Bywaters (a rheumatologist) noted that people rescued from bombed buildings in the Blitz who had been crushed by falling masonry, though not otherwise severely injured, remained anuric and died of acute uraemia. ‘Crush syndrome’ was later understood to be due to the toxicity of circulating myoglobin released from injured muscle.

In 1946, the first haemodialysis (HD) machine arrived in the UK at Hammersmith Hospital. It was only three years since Kolff in Holland had first used HD to treat ARF. Hammersmith obtained a Kolff-Brigham machine (an American modification of Kolff’s original). A small number of people with ARF were treated with mixed results.

There was still enthusiasm for non-dialysis management of ARF. Also, at Hammersmith Graham Bull (later professor of medicine in Belfast) deployed fluid and electrolyte restriction with a zero protein, very high carbohydrate fluid feed so disgusting it had to be given by nasogastric tube, with anything vomited going down the tube again! Some patients survived and renal function recovered. These were mostly single-organ ARF, rather than the catabolic multiorgan failure more often seen in modern practice. From the 1960s, acute peritoneal dialysis (PD) also began to be used for ARF.

Acute HD for ARF did not come into vogue again until 1956 in Leeds, the earliest continuously active HD programme. Other centres early to develop acute dialysis included Edinburgh, Manchester, and Guy’s. And notably the unit at RAF Halton, which for many years (until it closed in 1996) offered a mobile dialysis service around the southeast of England (and for service personnel around the world as well).

As kidney centres were established, care of ARF came to occupy a substantial proportion of the centre’s time. But compared to the increasingly well-defined funding and infrastructure for maintenance dialysis, the oversight of ARF care was often murky. Responsibility for its prevention and management involved primary care, and many areas of secondary care, especially acute medical and surgical specialities and intensive care. No direct funding streams were identified, and no responsibility for education and training in ARF care was defined. Whose responsibility was it?

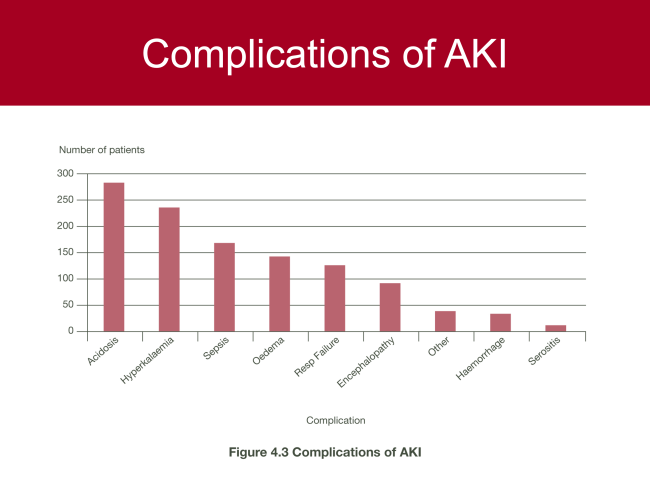

The Renal Association (now the UK Kidney Association) leadership took an important step in the early 2000s when they convinced NCEPOD (National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death) that the outcomes of AKI in acute hospitals deserved study. The NCEPOD Report ‘Adding Insult to Injury’ (2009) raised the risk profile of AKI, highlighting serious adverse outcomes and opportunities to improve care.

|

|

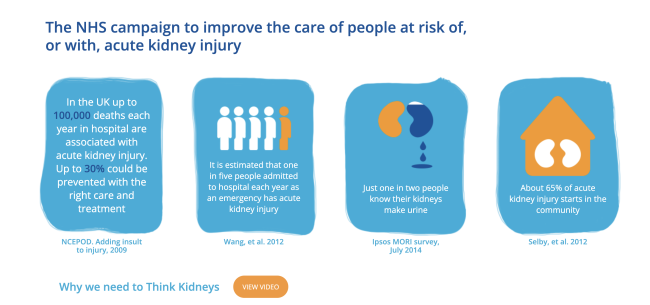

The NCEPOD report provided rationale and impetus for subsequent national initiatives (NICE AKI guidelines CG169 published in 2013) to improve AKI patient safety and outcomes, many driven by multi-professionals and patients from the UKKA and UK Renal Registry. An overarching aim of these campaigns, has been to herald AKI as a system-wide healthcare priority, vital and relevant for whole population health and multi-professionals in all healthcare settings.

The Think Kidneys programme (2014-2017) was an exemplar, so called to reflect its central aim for all healthcare providers and multi-professionals to promptly consider and mitigate AKI during acute illness episodes, similar to other serious system-wide patient safety risks, such as sepsis. Think Kidneys supported development of hospital-wide AKI care protocols, AKI nurse and pharmacist specialist roles, and much improved teaching and training about prevention and treatment of AKI. Notably, this campaign also helped develop and leverage national Patient Safety Alerts, aiming to standardise laboratory AKI detection (2014) and use of resources to improve system-wide AKI care (2016).

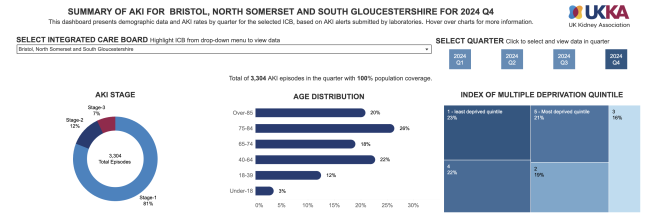

The mandate for hospital laboratories to use a standardised AKI algorithm to produce AKI warning stage alerts has not only promoted prompt recognition of AKI; it has also enabled the UK Renal Registry to maintain a national AKI registry (Master Patient Index), which remains unique world-wide.

A national CQUIN to support improved and timely post-AKI hospital discharge communication to Primary Care teams, followed in 2015-16, prior to publication of the Royal College of General Practitioners AKI Toolkit in collaboration with the Think Kidneys programme and partners, to support optimal AKI care in community settings (2017-18).

Plans to establish a UKKA AKI Specialist Interest Group (SIG) to further develop and maximise the impact of the Think Kidneys Programme, were paused in 2019 in order for this group to focus upon the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic imposed huge and serious AKI patient safety and healthcare system challenges, including the widespread increased need for kidney support in critical care settings. This risked a national shortage of materials required to enable vital kidney support, leading a group of 54 healthcare multi-professionals from the UKKA and Intensive Care Society to rapidly and collaboratively produce NICE-accredited guidelines to support best practice and service resilience (2020).

The UKKA AKI SIG was formally established in early 2021, and in 2025 comprises a membership of 90 healthcare multi-professionals who continue to promote and drive national AKI care and safety.